In these videos, you will be able to learn about the most interesting aspects of this room from the author himself.

Expand the titles in the image captions to enjoy each story.

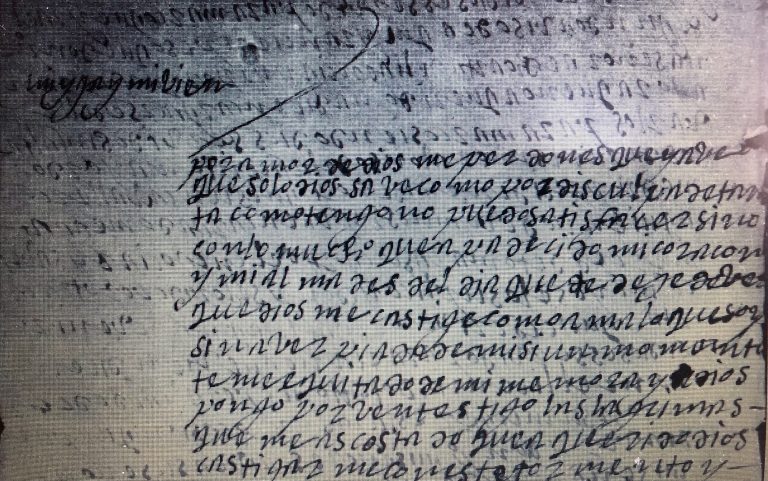

Many of the female passengers of the Carrera de Indias traveled thanks to the invitation of their husbands, who were already in the Americas. For this, they needed a “call letter” like this one, sent by a colonizer to his wife and presented by her to the Council of the Indies in order to obtain a license to travel to New Spain.

This letter was written by Pablo Domínguez from Mexico to his wife Catalina de Estrada, a resident of Seville (September 20, 1616).

It reads:

“My daughter and my dear; for the love of God forgive me, for I see that only God knows how, by excuse of all I have, I can only satisfy with the great pain that my heart and soul have endured since the day I stopped seeing you. May God punish me as the bad man I am, with no mercy upon me, if for a moment you have left my memory, and I put you as a good witness to the tears you have cost me, for God has wanted to punish me with this torment… My eyes, the hardship of the journey, are two months, and the arrival is very easy… My soul, I don’t want to tire you anymore, yours until death.”

Colonizers who were married and had left their wives in Spain could only remain in the Indies for a maximum of three years. If they did not return or manage to bring their wives to the Americas, they risked being fined or even imprisoned. Whether out of genuine affection and homesickness or to avoid these penalties, many of those adventurers wrote the famous “call letters,” wonderful epistles full of love, poetry, emotion, and passionate longing.

Thus, Antón de Beas, in 1517 from Mexico, pleaded to his wife Leonor, who remained in Sanlúcar de Barrameda: “Lady and wife, know that in you lies my life and my death…” or Antón Sánchez declared, in 1590 from Cusco, to his wife María de la Paz, who resided in Seville: “My wife of my life, I write you this with more desire to see you than to write you…”

In the painting, Don Blasco Núñez de Vela, the First Viceroy of Peru. After 68 days of navigation from Sanlúcar de Barrameda, he arrived at Nombre de Dios on January 10, 1544. His difficult mission was to enforce the New Laws of the Indies, decreed by Charles I, which protected the indigenous people by prohibiting their enslavement and even forbidding them from doing heavy labor. Additionally, the laws ordered the immediate elimination of the encomiendas. This provoked the first rejection and later rebellion of the encomenderos against the crown and its representative in the viceroyalty. Don Blasco died in the Battle of Iñaquito defending the rights of the Indigenous people on January 18, 1546.

The original painting, by an unknown author, is in the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru.

When wealthy merchants, nobles, and aristocrats traveled to the Indies with their families, they did so, as one would expect, under very different conditions from the common people. Some merchants could even travel on ships they owned, with cabins that provided them with privacy and comforts that the rest of the passengers could not even dream of. The distinguished gentlemen usually traveled on the escort galleons, the largest ships in the fleets. Although they were better fed and better protected from the weather and disease, they still faced hardships. Doña Beatriz de Carvallar, who traveled with her husband and daughter, wrote to her father from Mexico in 1574. After recounting the hardships of her journey and the serious illness she suffered – “I endured the cruelest diseases that any human body has ever seen” – she told him that she was now happy and settled with her beloved husband and daughter.

Lady Isabel de Bobadilla refused to stay in Segovia with her nine children (at least seven of whom were under 9 years old) when her fierce husband, Don Pedro Árias Dávila, the famous Pedrarias, was entrusted with the conquest and colonization of Castilla del Oro. Facing her temperamental husband, she insisted on accompanying him. Pedrarias insisted that she stay in the family home, and once he had arrived safely in the new lands and settled the colonists, he would send for her. But to be the wife of Pedrarias, one had to rise to his level, and Doña Inés, not intimidated by either her husband or the harshness of the journey, said: “Wherever fate takes you, whether among the furious waves of the ocean or in the horrible dangers of the land, know that I will accompany you… it is better to die once and be eaten by fish or go to the land of cannibals to be devoured than to waste away in mourning and perpetual sadness waiting, not even for my husband, but for his letters… choose one of the two: either cut off my neck or agree to what I ask.”

The crown promoted the passage and settlement of farming families, offering them all kinds of benefits: free land and exemption from taxes, but also the prohibition of abandoning them for four years. The high cost of the passage, the fear of crossing the sea, and undertaking the terrible voyage meant that only a few families took the enormous risk of doing so.

They all traveled.

This painting is called La familia. It was painted by the Cuenca-born artist Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, a disciple and son-in-law of Velázquez. It is an oil painting on canvas measuring 150 x 172 cm. The original is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

The photograph was taken by Ángel Benzal Pintado inside the ship Nao Victoria. This vessel belongs to the Nao Victoria Foundation. For more information:

In addition, lice and bedbugs thrived unchecked, constantly biting and disturbing the passengers, while also spreading typhus, a disease that devastated the ships’ crews and passengers.

Imagine the experience of someone with a fear or disgust of mice, rats, lice, or bedbugs—can you picture feeling them crawl over your body while trying to sleep? And this happening for days, weeks…

The combination of consuming contaminated or spoiled food, insect bites, drinking bad water, overcrowding, and the lack of hygiene created the perfect breeding ground for all kinds of diseases. Particularly food poisoning and gastrointestinal illnesses. In the letters found by the researcher and Hispanist Enrique Otte, he uncovered data such as the following:

“There is no fleet that does not reek of pestilence; in the fleet we came with, the people were so decimated that only a quarter remained” (OTTE 1996: LETTER 56).

“[…] In the fleet we came with, two-thirds of the people who set sail died” (OTTE 1996: LETTER 57).

Only God knows how many people, weakened by illness and malnutrition, would die in solitude on the ship’s decks.

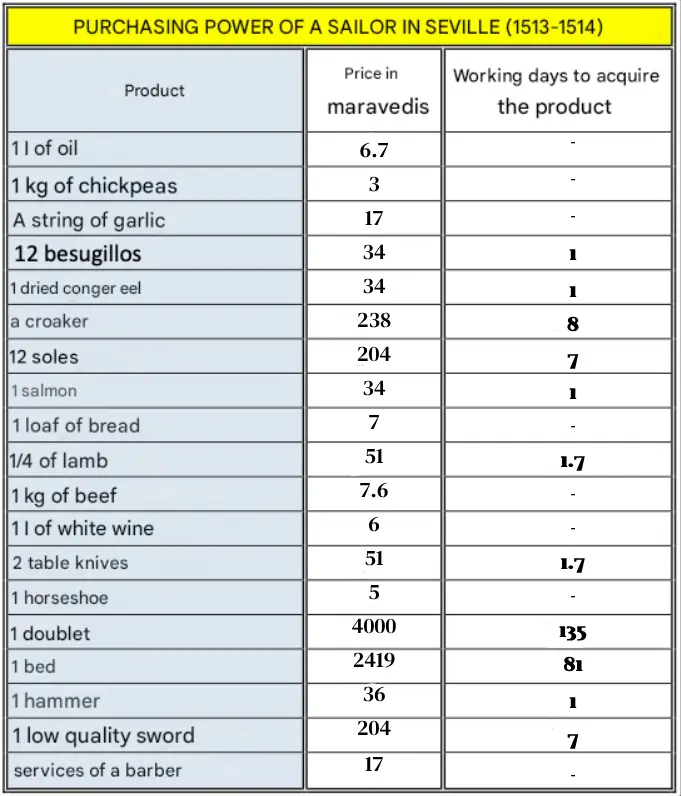

To board one of the ships departing from Seville to the Indies, one first had to arrive in Seville, often navigating the difficult and dangerous roads of the 16th century. Travelers had to provide for not only the voyage but also the costs of food, lodging, and unforeseen expenses along the way. This was not within everyone’s reach, and many passengers had to pawn or sell everything they had to make the journey. Those who managed to reach Seville then had to survive there, waiting for days on end to secure embarkation permits and for the departure of the fleets, which never had a fixed date. It depended on the whims of the weather and the strategic decisions of the merchants from the Casa de la Contratación. As rumors spread that the departure date was approaching, prices would rise, supplies and provisions would dwindle, and the chances of finding accommodation became slimmer. What little accommodation remained was at exorbitant prices.

In addition, the city, full of merchants and passengers, would become rife with opportunists, rogues, thieves, swindlers, and all kinds of people who made a living off the misfortune of others, preying on the inexperienced souls hoping to sail to the Indies. Thousands of the unfortunate would return home ruined, if not wounded. Many more would find their only passage was to the other world, succumbing to death on the crowded streets of Seville. In years like 1649, a terrible epidemic of bubonic plague claimed nearly half the population, including those awaiting embarkation. The economy of the city and the Carrera de Indias itself would suffer the consequences of this tragedy for decades.

“There, they say, lies paradise. A mythical place where everything is possible… Perhaps mountains of gold and abundant manna. Precious pearls, beautiful women… But it’s just celestial music, a siren’s song that deceives ships, never to return.Believe me, adventurous friend, if I were you, even though you hear that music, I wouldn’t let myself be dragged in… For anyone who offers you much through hearsay, and shows no proof of what they speak of, surely seeks something from you for their own gain. For you, you risk your ship, while they don’t even move a boat.”